SEE What's going on in Pepin County >>>

Art, Music, Cultural Events, and more!

History in Pepin County

Step back in time in Pepin County, where history comes alive through preserved architecture, museums, and historic sites. Best known as the birthplace of Laura Ingalls Wilder, our region tells stories of Native American heritage, early European settlement, and river town development. Explore historic downtown districts, visit authentic pioneer sites, and discover the rich tapestry of Mississippi River culture. Experience how our past shapes the present while creating your own memories in our historic communities.

OUR BEGINNINGS

Read More

Pepin County was created by a special act of the Wisconsin Legislature on February 25, 1858; ten years after Wisconsin became a state. Before that, Pepin was part of Dunn County, and before that, part of Chippewa County. The lands including Pepin County were acquired by the Federal government by treaty with the Dakota peoples in 1837.

Pepin County History

The indigenous people lived here thousands of years before the first European explorers ventured into the region. Our information on the culture and lifestyles of the indigenous peoples who were here first is limited due to a lack of written information.

Most of the information we have is what has been found in their village dumpsites and their graves; broken pottery, arrowheads, animal bones, beads, kernels of corn and seeds…things that tells us what they ate, how they hunted, how advanced they were. Here in Pepin County there are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of ancient burial mounds, some of which have been dug up and historic artifacts removed.

The Native Americans also left us some of their oral history. Stories were passed from one generation to the next through songs and poems, which were likely overheard by or translated for the early European explorers, missionaries, and traders, giving rise to many myths and legends about the pre-historic people. One such story is the “Legend of the Maiden Rock”.

During the past 200 years, many versions have been written about the tragic suicide of a young Native American woman, whose father refused to permit her marriage to a brave from an enemy tribe. The bluff from which she threw herself, the Maiden Rock, has been a Lake Pepin landmark for river travelers for centuries.

EXPLORERS

Read More

Pierre Esprit Radisson

The Eastern Dakota were the principal inhabitants of this region when the first European explorers began to arrive. These explorers kept journals and diaries and wrote letters about their adventures. With their arrival, Pepin County’s written history began.

Pierre Esprit Radisson, an early French explorer, is believed to have been writing about the Eastern Dakota in his journal in the mid-1600’s, referring to them as the “Nation of the Beef”. He described them as living in a town with large cabins covered with skins and mats. They subsisted by hunting bison, large herds of which are believed to have roamed the Chippewa River Valley, and which may explain why Radisson called them the Nation of the Beef. They also harvested wild rice and other abundant flora and fauna of the riverine environment.

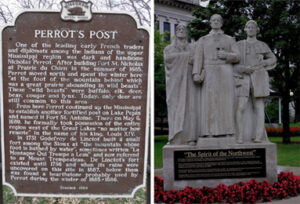

Perrot’s Post

Another Frenchman, Nicolas Perrot, described the Eastern Dakota as living in swampy territory, “…nothing but lakes and marshes full of wild oats…in a tract 50 leagues square with the Mississippi River flowing through the middle.” Perrot could have been talking about the Chippewa River delta at the foot of Lake Pepin.

By the mid-1600’s, the French had begun to send expeditions into Wisconsin via the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. King Louis XIII of France is believed to have granted a huge piece of land in the Upper Mississippi River Valley to two brothers, Etiene Pepin de la Fond and Guillaume dit Tranchemontagne. Two of Gillaume’s sons, Pierre Pepin and Jean Pepin du Cardonnets, later explored and traded in this area, and their name somehow became attached to the lake, and ultimately to the village and the county.

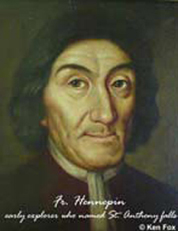

Father Louis Hennepin

In February, 1680, Father Louis Hennepin and two lay Frenchmen, Anthony Augelle and Michael Accault, set out in a birch bark canoe to explore the upper Mississippi River. On April 12th, soon after their arrival at Lake Pepin, they were taken captive by a band of the Assati Sioux (Dakota). During two months of captivity, they were taken up the Mississippi as far as St. Anthony Falls. Hennepin preached the gospel to his captors and accompanied them hunting buffalo. Eventually, the three Frenchmen were given a canoe, a gun, a knife, and a robe of beaver skins and were released. They started back down the Mississippi, continuing as far as the mouth of the Chippewa River. By Hennepin’s account, they ascended the Chippewa to the mouth of another river, which was likely the Eau Galle or the Red Cedar. Hennepin and his companions were the first white men to see the site of the present City of Durand and the surrounding area.

In 1686, Nicolas Perrot, standing along the shores of the Lake of Tears (later Lake Pepin), claimed in the name of the King of France, all the land that drained to the Mississippi River. Perrot built a stockade to serve as a fort and trading post on this site, a prominence offering a broad view of the river, protected by the bluffs, and sloping gently down to a quiet bay. An archeological survey conducted in 1994 verified French presence on just such a site located within two miles down river from the present Village of Stockholm. For years, it has been believed to be the site of Fort St. Antoine, Perrot’s premier fort on Lake Pepin. However, the artifacts found in 1994 were more consistent with those of the French of the 1720’s, rather than 40 to 50 years earlier.

French trappers and traders dominated commerce along the Mississippi River for the next hundred years, despite British attempts to move into the area. The French influence in Pepin County continued with the opening of the Chippewa River Valley for logging in the 1800’s. French Canadians arrived in such numbers, they became the founders of many villages in the area. In Pepin County, they built their homes in and around the Arkansaw-Porcupine region. Birth, baptismal, and marriage certificates from the earliest days of European settlement in the area recorded dozens of French surnames, many of which continue to be recorded today.

French trappers and traders dominated commerce along the Mississippi River for the next hundred years, despite British attempts to move into the area. The French influence in Pepin County continued with the opening of the Chippewa River Valley for logging in the 1800’s. French Canadians arrived in such numbers, they became the founders of many villages in the area. In Pepin County, they built their homes in and around the Arkansaw-Porcupine region. Birth, baptismal, and marriage certificates from the earliest days of European settlement in the area recorded dozens of French surnames, many of which continue to be recorded today.

John McCain is believed to have been the first European to settle in this county. He built the first home here in 1846; a small log house on a parcel of land located about two miles west of what is now the Village of Pepin. He was of English-Scottish descent, born in Pennsylvania in 1814. McCain lived on his Pepin County farm until his death in 1887. He was reported to be a tall, powerful, well-built man ready to face any danger and hardship. Historical accounts also indicate he was a favorite with children to whom he was known as Uncle Mack.

Alexander Babatz

W. B. Newcomb arrived the same year as McCain and built a cabin in what is now the Village of Pepin. During the mid-1800’s, Pepin was the jumping off point for lumberjacks and other men looking for work in the great white pine forests to the north along the Chippewa River. Early entrepreneurs saw Pepin’s potential to become an important river port. The gently sloped riverbank served early vessels well; however, the water was too shallow to accommodate the larger boats, which came later in the century.

Alexander Babatz arrived in Pepin County about 1850 and was the first settler on the site of the present day City of Durand. In 1856, Miles Durand Prindle set out from New England with the express purpose to establish a town. He founded his town on the east bank of the Chippewa River twenty miles upstream from the Mississippi on land he acquired from the Federal government. Prindle named it after his mother’s maiden name.

HISTORIC LOCATIONS

Read More

Meanwhile, the Wisconsin Legislature carved Pepin County from Dunn County, named the Village of Pepin the first county seat, and appointed Henry D. Barron the county’s first judge. The first term of court was held in the spring of 1858.

By 1860, Durand had grown dramatically and, by virtue of a majority of voters in the county, laid claim to the county seat and obtained leave to test the question at the polls. It lost that year, but the question was brought before the voters again, and it won. In 1867, Durand was declared county seat following a lawsuit decided in La Crosse County Court.

In 1871, Miles Durand Prindle offered the county one-and-a-half acres of land in Durand for the sum of one dollar in return for a promise that a courthouse would be built within five years. Construction of the new courthouse was begun in 1873 and completed in 1874 at a cost of less than $12,000. Nonetheless, the location of the seat of government for Pepin County remained unsettled for years to come.

In late 1881, voters approved removal of the county seat to Arkansaw, an unincorporated village three miles west of Durand, which had also seen considerable growth and development. A proclamation by the governor made the transfer official on December 15, 1881. Another vote taken in 1882 reaffirmed the wishes of county voters to keep the county seat in Arkansaw. For the next five years, a large frame building in Arkansaw was rented by the county and used as a courthouse.

Miles Durand Prindle was understandably upset by these events, especially when the county board of supervisors, after vacating the premises, moved the District Attorney’s office into the now empty courthouse building in Durand. One day, while the D.A. was out of his office, Prindle locked and secured the doors, claiming the conditions of his deed had been broken.

Pepin County filed a lawsuit seeking repossession, but the judge ruled in favor of Prindle. He eventually transferred the property to a group of four businessmen, who subsequently deeded the building to the Village (now City) of Durand. In 1886, Durand transferred the building back to Pepin County, following yet another vote, which moved the county seat back to Durand once and for all by a vote of 937 to 618.

Pepin County filed a lawsuit seeking repossession, but the judge ruled in favor of Prindle. He eventually transferred the property to a group of four businessmen, who subsequently deeded the building to the Village (now City) of Durand. In 1886, Durand transferred the building back to Pepin County, following yet another vote, which moved the county seat back to Durand once and for all by a vote of 937 to 618.

The stately courthouse, which today is the only remaining wood-framed courthouse in Wisconsin, served the people of Pepin County for 110 years. This gracious old building today stands proudly on Washington Square, a testament to the strength and devotion of the citizens of Pepin County and the City of Durand. The Old Courthouse Museum and the Jail are both on the National Register of Historic Places. Link to Old Historical Courthouse Museum.

The year 1881 was a particularly tragic year for the then-village of Durand. The removal of the county seat to Arkansaw in late 1881 was preceded by the hanging of Edward Maxwell by an angry lynch-mob on the courthouse lawn on November 19, 1881. The lynching climaxed a sensational nation-wide manhunt for Maxwell and his brother, Alonzo, following a shoot-out the previous July in Durand that killed two local law enforcement officers, brothers Charles and Milton Coleman.

The Colemans, both highly regarded family men, were the first two law officers to die in the line of duty following Wisconsin’s statehood. Ed Maxwell was captured in Grand Island, Nebraska, and brought back to Durand to face charges.

Immediately following the adjournment of a boisterous preliminary hearing in the upstairs courtroom of the Pepin County Courthouse, some members of the audience spontaneously formed a mob, subdued peace officers quickly, grabbed hold of Maxwell, got a noose around his neck, drug him down the stairs, out the door, across the porch and down the steps of the courthouse, and up a tree. The mob violence ended quickly. After a few moments of stunned silence, the angry mob slowly dispersed. The event created a public image of Durand as a “hangin’ town”, which affected it for years to come and likely influenced the voters’ decision to re-move the county seat to Arkansaw.

Climaxing the events of 1881, the worst fire in its history wiped out most of Durand’s downtown on Christmas Day. The fire destroyed 34 businesses, many of which were under-insured. During the subsequent reconstruction, the previous wood-framed buildings consumed in the fire were replaced with brick and mortar structures. Fortunately, the wood-framed county courthouse stood apart from the other buildings downtown and survived the fire.

Pepin County

Office

740 7th Avenue West

Durand, WI 54736

Contact Us

(715) 672-7242 X146

info@co.pepin.wi.us